The Basics for Building and Maintaining Incentive Plans at Smaller Firms

Most company leaders recognize that incentives are a critical part of total compensation. But once in place, incentive programs often do not change to accommodate employees’ needs, a shifting economic landscape, or sometimes both.

For rewards to be effective, they must create increased focus on the part of participating employees. This focus is a direct result not only of financial reward but also of a positive work environment and the path that the company owner has drawn for the personal and professional development of employees. Money is unquestionably motivating, but so is an atmosphere where a culture of confidence exists.

Frequently, incentive programs do not go the distance because they were weak from the start. The development of an effective incentive and compensation program is rooted in a company’s vision for the future and the role key employees will play in those expectations.

The Discovery Process

Identifying and solidifying key compensation philosophies and priorities is at the heart of a great incentive plan. This discovery process helps achieve a unified financial vision for growing the business. It can also distinguish the relationship between company and employee wealth building goals, establish the framework for an employee and executive compensation philosophy, identify factors that will drive desired performance and create a prioritized plan of action for strategy development. The discovery process is best described as a comprehensive set of recommendations to begin designing a total rewards program uniquely suited to support a company’s short and long-term strategic objectives. It also directly responds to the needs and desires of the individual members of the company’s executive team.

The importance of a rewards program that addresses the vision of both the company and the individual employee cannot be overstated. Far too often a disconnect exists between the two entities. Personalized incentive programs should be continually assessed, adjusted, analyzed and adapted to ensure top level employees have their eyes on the same prize as the company owners.

That prize is typically one of two scenarios—building and growing the company for the long term or bringing it to a point of success that will attract a buyer. Although employees might fully comprehend this vision and recognize the connection between the company’s targets and the achievement of their own goals, the bottom line for most employees is likely drawn more with salary, benefits and job security in mind. However, a thorough discovery process may unveil other areas of incentives not considered by company owners.

Gathering the Data

The discovery process is best conducted by an impartial party by means of interviewing key executive and management personnel. Interviews must be conducted in a highly confidential manner, allowing participants the proper sense of comfort to speak frankly about their personal goals within the organization.

The data gathered should address the business owner’s vision for the future in addition to wealth building objectives. Also vital to the data gathering process is input on growth expectations, including factors and names of individuals that will affect these expectations. Key staff members should also be asked to specify their individual objectives in relation to the company’s performance and anticipated growth.

This process helps ensure that the company’s compen sation philosophy and design is built on a proper and last ing foundation. It can also yield dividends in the evolution and implementation of an incentive and compensation plan that will attract and retain key talent.

Compensation Criteria

Compensation can have many meanings—payment, reward, advantage, opportunity. And when it comes to retaining key executives who can help a company achieve growth and prosperity, all these definitions must come into play.

Companies often do not realize their full growth potential because they have yet to develop an incentive program that truly motivates employees. Although “motivation” in the business world is often a euphemism for “more money,” most executives would likely agree that it takes more than a hefty paycheck to keep them satisfied.

As Thomas Alva Edison once said, “What you are will show in what you do.” These words ring loud and true within a company’s structure and illustrate the importance of matching the skill sets and talents of key executives to their appropriate role within the organization.

Avoid the “Cookie Cutter” Approach

Savvy company owners recognize that most employees are motivated by similar elements—an atmosphere that encourages skill development, active participation in decision making processes, opportunities for professional growth and a comfortable living now and in retirement. But they also understand that each member of their executive management team is unique and has distinctive needs.

The imperative is to distinguish how to best provide the tools needed to affect individual growth and company devotion. Company owners should be specific as to the importance of an individual’s contributions and how they benefit and reflect positively on the company. They should then take into account the best way to motivate that individual through a personalized incentive package tailored to each key employee’s situation and goals.

For example, executives often have a desire to accumulate more retirement savings than qualified retirement plans, such as a 401(k) can provide, and they also want to do so with tax efficiency in mind. Long-term incentive plans should consist of a number of components to pro vide executives a diversified package. The more attractive this package is, the more difficult it will be for key employees to leave a post for other opportunities.

To be empowered and excited about their work, their role within the company and ultimately the company itself, key employees must feel part of the entire process; in other words, they must be encouraged to embrace an owner ship mentality. They need to know where the company is headed, strategies to get there, how they can participate in achieving company goals, and last, but certainly not least, what’s in it for them..

Pay for Performance

The most successful incentive plans are structured around a pay for performance philosophy, one that includes numerous specific objectives. These goals include but are not limited to recruitment and retention of the highest quality employees; communicating the organization’s values and objectives; creating employee ownership and engaging staff in the overall success of the organization; and the development of a reward mechanism for individual and team achievement.

To meet the objectives of a compensation program with pay for performance as its focus, the following essential criteria must be met: awards are tied to shareholder financial objectives; the proper mix of compensation elements is in place; the plan encourages employees to achieve specific goals; the plan is effectively communicated, reinforced and regularly reviewed and reevaluated.

The company must determine the amount of award, a roster of participants, a standard for earning the award and when the award will be paid out. Also, a balance must be defined between company, team and individual performance.

Creating Line of Sight

Seasoned professionals understand that purpose or specific goals must first be defined, based on specific needs, such as increased sales, improved customer retention or particular margins. This fundamental element of a solid incentive program is sometimes overlooked by even the most veteran business heads. Without a clearly defined plan, lines of communication can be thwarted, resulting in damaged employee morale and ultimately harm to the company. A plan that unmistakably spells out the ratio between performance and rewards creates a line of sight for an employee—not only about his or her specific function within the organization but also how it ties into the company’s overall vision for the present and the future.

Seeing Eye-to-Eye

Ultimately, company owners/shareholders and employees want the same thing—for the business to endure over the long term and maintain prosperity throughout. How ever, their visions regarding incentives often do not have the same focus.

Company owners most commonly want to grow share value, maximize abilities of key employees, minimize liability and exposure to risk, provide a quality product/ service, recruit and retain talented staff, build a legacy, exit the business and unlock equity.

Common incentive themes among employees include developing and utilizing unique abilities, receiving rewards for superior performance, enhancing income and growth opportunities, protecting their families financially, providing for their retirement, participating in the growth of the company, earning opportunities for professional growth and building wealth.

For rewards to be effective they have to create increased focus on the part of participating employees. This focus is a direct result not only of financial reward but also of a positive work environment and the path that the company owner has drawn for employees’ personal and professional development.

Identify Incentive Recipients

Determining which employees are best likely to achieve the company’s “best results” vision requires significant consideration and observation. Not every employee is able to fulfill these initiatives and the role of some employees is not equal to that of others. Incentive recipients are typically those C-level or management tier employees who can best provide input to achieve company-defined results.

Defining initiatives and projecting a timeline for achievement will assist in deciding which staff members will be assigned to accomplish set goals. This process will also help to determine which employees will achieve a greater impact as an individual contributor or team member.

Defining Indicators

Seasoned corporate professionals recognize that the fundamentals of a good incentive plan include the elements of vision, potential, communication and motivation. A sound incentive program projects the potential that can be realized if incentive promises are fulfilled—by both emp loyer and employee. However, in the absence of well defined indicators and a “best practices” framework for the long term, even the most comprehensive program can fall short.

Indicators, which are sometimes referred to as measures and metrics in a company’s reward strategy, are pivotal to a comprehensive incentive program. Indicators are not to be confused with motivators; motivation is an external element, best encouraged by aligning employees with roles and tasks that are consistent with their abilities.

The role of indicators is straightforward: They seek to improve performance, influence behavior and create focus. These far-reaching elements can only be accomplished through communication and consistent reinforcement that promotes a companywide mindset of employee owner ship. Without a base of thoroughly defined indicators, employee motivation can collapse, creating a domino effect that can negatively affect a company’s structure and culture in short time.

To create a culture where employees think like owners, a “best practices” framework that addresses a number of issues should be in place. Key among those issues is how company growth is defined; the baseline on which contributions to the profit pool will be based; payment threshold; percentage to be shared; an allocation formula; and a definition of the expected individual’s performance.

Companies must match incentive programs to their culture, business model and goals. Great companies gen erate great results by focusing employees on achieving great goals. But to realize that end result, rewards pro grams must be reviewed regularly to determine whether what worked yesterday still works today, particularly in light of the current economic landscape.

Quantify the Value

The process of quantifying the value created when incentive objectives are met typically requires construction of a model that projects base, target and superior result thresholds.

Executive compensation should consistently revolve around two key questions: Is the right amount of compensation paid out to motivate and focus senior staff on the company’s strategic objectives? Is compensation properly aligned with shareholder interests?

Individual salaries encapsulate numerous factors, including historic and incumbent-specific factors. As such, competitive pay data should be used as a guide for establishing acceptable ranges. Other factors to consider when deter mining appropriate pay ranges include forgone compensation, individual contribution, roles and responsibilities, knowledge, qualifications, profitability, other elements of compensation and internal equity. Once the economic value has been determined, the amount that is shared with employees must be addressed.

This can be achieved by settling on an acceptable “target” pay-for-performance return and then through earmarking an achievable “superior” return. When these two measures are identified, an incentive goal can be established.

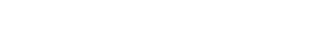

The next step is to determine a standard that defines the potential value in current terms. The potential reward, then, might be stated as a percentage of contributors’ cur rent salary—of course, the big question is the percentage amount. Incentive plan targets that combine the short and long term will likely be in the 60% to 80% of salary range for top managers and between 40% and 80% for second tier managers (see Table 1).

Establishing Tiers

Establishing tiers is vital to a comprehensive incentive program because not everyone has an equal part in creating increased value. A business needs to define tier levels and assign participating employees. By establishing various levels, the company can assign greater potential value to those who will have the greatest impact.

Weighting—or determining how much of a reward should be assigned to the achievement of various categories of expectations—is part of the tier concept. Weighting should be based on the impact an employee’s role makes on these expectations.

As an example, reward an executive in the Tier1 level might be based on 75% for company performance and the remaining 25% for individual achievement, thereby excluding team requirements. Conversely, a manager in Tier 2 could have a weighting allocation of 25% to company performance, 50% to team and 25% assigned to individual achievement.

Determining Allocation

It is imperative to decide when awards will be paid out— at the end of the quarter, end of year and/or sometime down the longer road. Typically, a percentage of total incentives are paid annually and a percentage rewarded in the future; however, the payout can vary by tier.

Those in the Tier1 bracket might receive 50% of incentive over a short period of a year or less and the remaining 50% over a longer term in the 3 to 7year range. Tier2 employees might have 70% of total incentive paid over the short term and 30% allocated to long term.

Another form of executive incentive is the performance unit—an offer to pay an executive a sum of cash at the end of a long-term performance period. The amount is based on the consistent attainment of certain preestablished financial objectives set by the company owners and/or share holders. Some may define this brand of incentive as the definitive performance carrot as it encourages an executive employee to tie individual success to that of the company. There also exist a number of long-term rewards programs with the payout made in 5 or 10 years and sometimes not until an executive’s retirement.

Total Rewards Targets

A total rewards target represents the ideal blend of pay for different levels of employees. Although it may never actually reach the ideal, it serves as a guideline for management to consider when structuring pay arrangements for employees at different levels within the company.

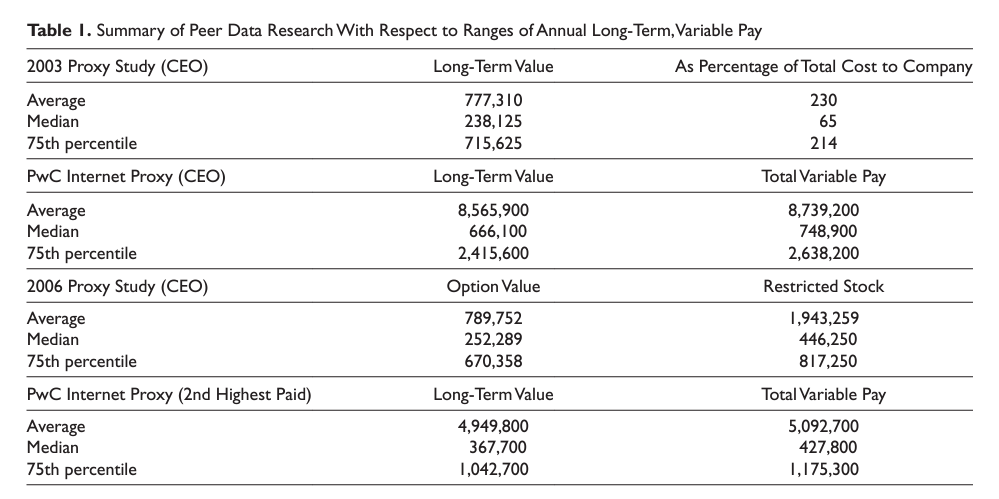

To establish a total rewards target, the company must define short and long-term rewards and determine what portion of an employee’s compensation and benefits package should be fixed and what portion should be variable. Fixed plans include salary, core benefits and contributions to retirement plans whereas variable plans generally include bonuses and long-term incentives, including cash and equity.

The total rewards target represents the ideal allocation that will produce the highest return for the company. The allocation of pay will influence behavior so that the return is measured by optimal employee productivity. Because optimal productivity correlates directly to profitability, shareholder value will increase (see Table 2).

Prescribe the Measurement

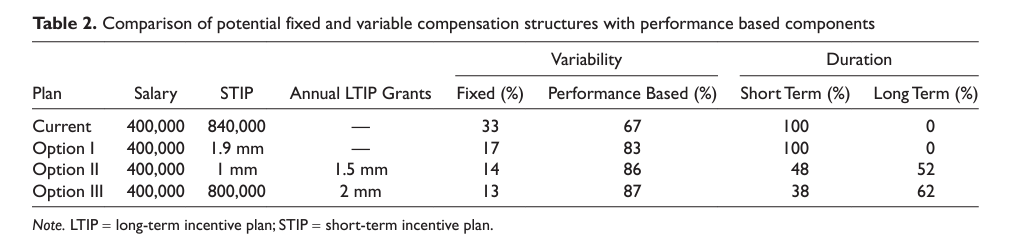

Determining how the long-term portion of the incentive will be measured over time caps a compensation pro gram. This could take any number of forms. For instance, it could be held in a pool; credited with interest or investment earnings; or treated as a stock or phantom stock incentive.

With this type of incentive program in place, share holders know the precise value accrued before managers earn incentives. They know the percentage of future growth shared with the management team, and they also know managers will be rewarded for achieving specific and measurable results. Companies can work through a “decision tree” process to determine the most appropriate mechanism for payout consistent with desired results (see Figure 1).

Performance, Compensation and the Recession

The pace may slow significantly, but even in the wake of a recession, high-performance organizations tend to advance as long as they maintain the foresight and often the courage to make what may appear like counterintuitive decisions during difficult economic cycles. That ability to stay the course with a historically prudent strategy is what gives some companies the edge even during times when competitors are in defensive mode.

Shrewd business owners recognize that in both good times and bad times, the most critical key to success is their talent pool. Likewise, they are also well aware that it is precisely at the trough of a recession that the labor pool will be at its deepest and wage pressures at their lightest.

Regardless of the economic climate, the highest performance organizations look to hire and retain employees that will commit to the company’s vision and strategy. They want top talent with that vital ownership mentality.

The most talented individuals respond to a workplace that rewards based on performance. Toptier employees not only recognize but also respect the balance that exists between long and short term compensations. They understand the economic outcomes the company needs to achieve for sustainability and growth and are also aware that although anemic economic conditions may affect the shape their compensation package takes now, that shape will take better form as the economy improves.

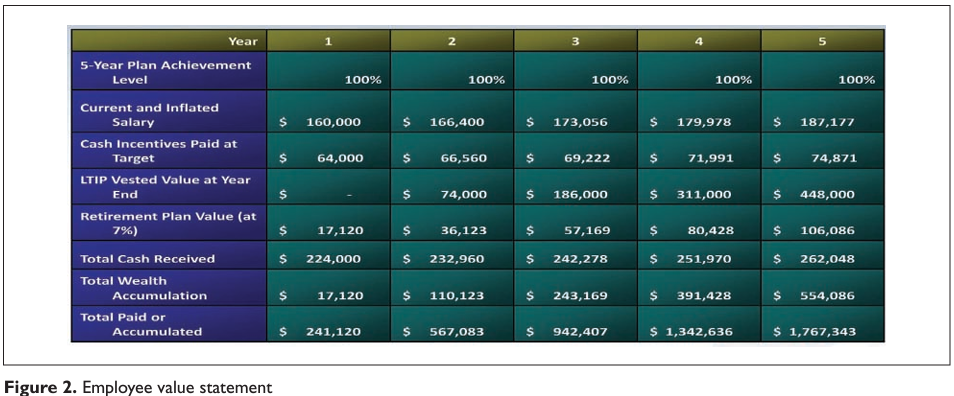

A compensation structure that attracts high-echelon workers addresses the primary need for sustainable cash flow, security and wealth accumulation, both for today and the longer range (see Figure 2).

Evaluating Compensation Structure

The present economic climate offers an opportunity to evaluate the compensation structure and make necessary adjustments to accommodate various challenges, whether recessionary or otherwise. When business is on an upward trend, salaries are at or may even be slightly above mar ket; short term incentives are equal to a percent of salary; and longterm awards are based on market guidelines. Conversely, when business is trending down, salaries are at or slightly below market; short term incentives are minimal; and long-term awards are higher than market levels. Businesses that adopt these compensation philosophies have the capability of interjecting practical solutions when the economic flow is downward.

Recessionary periods often engender reactionary response, such as layoffs or the euphemistic “reduction in force.” But a company with a thoughtful compensation philosophy may consider other cost-cutting measures that in the long run could assist in retaining top talent. For example, sabbatical leaves might be offered to certain employees instead of a cut and dried layoff. This short term furlough will reduce or suspend salary, but keep employees eligible for long-term benefits and wealth building programs.

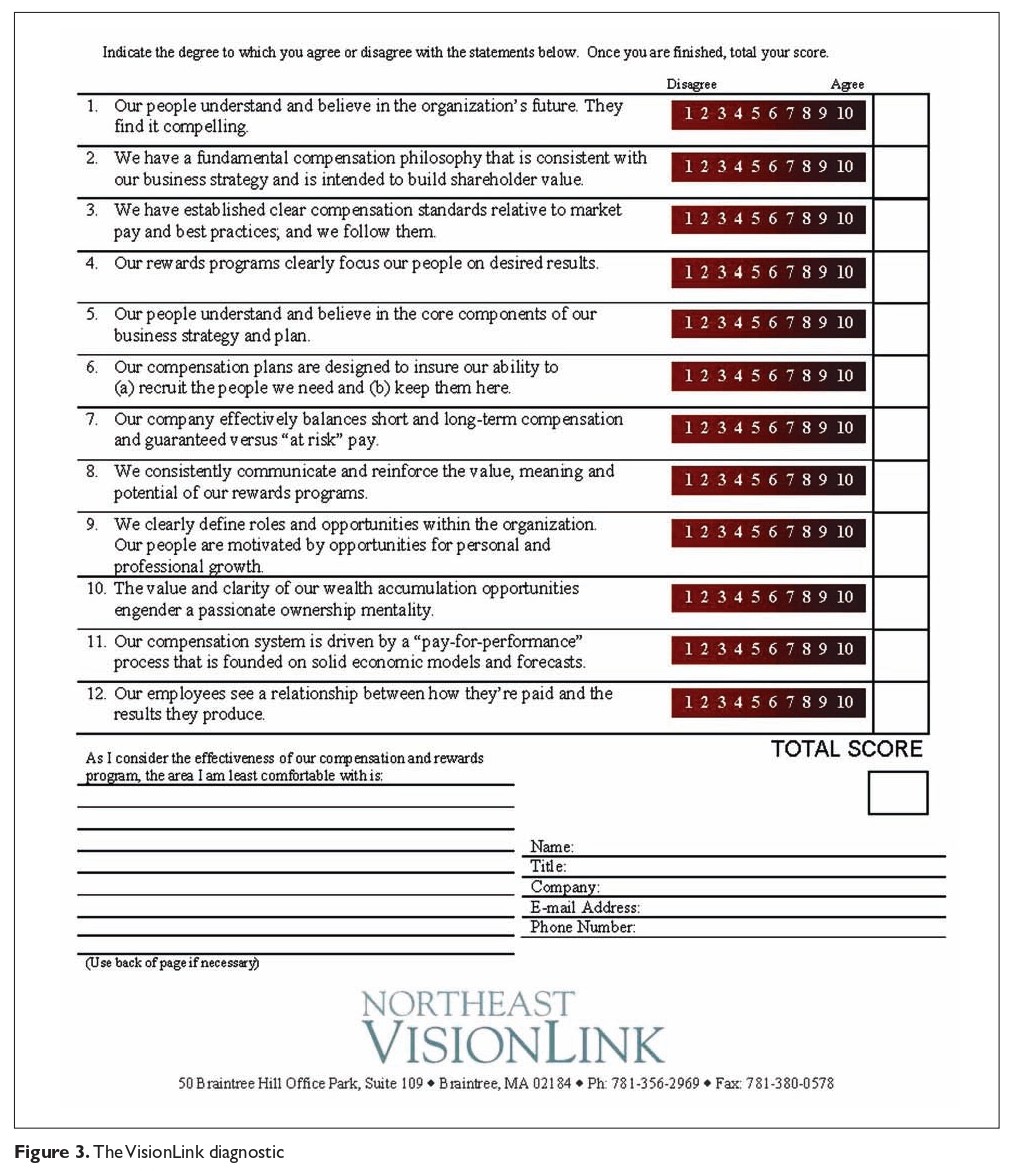

Tiered pay cuts are another measure to reduce costs and retain key employees during challenging economic times. Top-quality team players will recognize these adjustments in salaries as a necessary means to maintain jobs. And during poorer performance cycles, a company might eliminate bonuses or raises, instead granting additional stock options. Employees who have embraced an ownership mentality will comprehend that shifting financial circumstances may redefine their compensation and short term rewards. And if dealt with honestly and fairly, they will maintain their focus to achieve company goals with the knowledge that better times will eventually return (see Figure 3).

When It’s Not Working

Even the most well intentioned incentive programs can fast approach the edge of failure in the face of specific obstacles. An unclear definition of the company’s future is a major impediment to the success of an incentive pro gram. When plans for the future are not effectively communicated, employees often don’t see a role for them selves beyond the short term, leading to feelings of being “kept out of the loop” and a sense of insecurity.

Other barriers are created when the company has not established a consensus about how to use rewards pro grams to accelerate company growth. And in some cases, a rewards philosophy has been developed, but not properly communicated to employees. And then there are those incentive plans that are incomplete or simply inadequate. While these barriers can make or break an incentive plan, other indicators that a rewards strategy is not working are even less subtle.

Maintaining Focus

The framework of an incentive program becomes com promised when the company does not view compensation as an investment, but rather as an expense; as such it has no way to track and measure the return on the investment. The fundamental focus of an incentive plan becomes blurred when the full potential value of the total rewards package is not regularly and powerfully communicated and when some but not all of the elements are built to generate “line of sight.”

Failure can also lurk when company tradition is to build rewards plans separately for individual employees and not on an integrated team basis. And the absence of clear standards and methods to set and reset values that are consistent with employee expectations may prompt key talent to leave if offered a better value proposition elsewhere.

In It for the Long Run

Incentive plans—even the most successful ones—must be reviewed and reevaluated periodically to ensure relevancy. Those that remain unchanged for long periods of time may weaken their goal to motivate and/or assume entitlement status. Incentive plans that become stagnant can engender a company culture where employees con figure their performance to meet the minimal needs of the plan, rather than fulfilling the company’s maximum business needs.

Often, the very foundation of a company is its executive employees. Engaged and committed management staff members will become even more invested in their roles and exhibit increased entrepreneurial spirit if company owners clearly communicate expectations, articulate growth strategies and reward key employees based on how well the company performs.

Although rewards or incentives can be finetuned to specific employee needs, they should always be linked to the company. For example, instead of writing out a quick cash bonus, consider long-term incentive programs such as phantom stock. This type of reward is directly tied to the success of the company as a whole and generates a “team” culture.

Eliminate Entitlement Culture

An incentive program that automatically includes a holiday bonus can lead to a sense of entitlement, yet the antiquated concept of handing out cash gifts lingers for many companies. This yearly reward is often looked upon as a component of salary, essentially diminishing the true definition of performance incentive.

Although the intention may be to create a sense of seasonal buoyancy, this across-the-board reward mechanism not only can lead to a culture of entitlement, it can also alienate certain employees whose performance is consistently outstanding. Worse still, it could prompt them to move on to newer prospects.

On rare occasions, a well timed spontaneous reward can go a long way toward building employee morale. For example, a check for a modest amount in the aftermath of a specific company success can impart management members with a sense of company loyalty. Certainly bonuses such as these can promote short term allegiance, but they should be used more as a motivation tool, inspiring key employees to maintain an active and long term role in the organization’s growth.

Changing With the Times

Incentive programs should be reevaluated and refined in accordance with shifting organizational goals. Over the course of time, a company’s mission may change. For example, a business that aimed to go public 5 years ago may today be looking to merge with another company or to out-and-out sell.

Incentive strategies must be made to fulfill the visions of both company owners and their executives. Business leaders should challenge key employees to their highest potential, always at the ready to provide accolades intime of individual and team success and share the responsibility in the wake of failures. Ultimately, the develop ment of personalized incentive programs must be tied into a company’s vision—one that should be continually assessed, adjusted, analyzed and adapted to ensure top level employees have their eyes on the same prize as the company owners.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Bio

James E. (Jim) Moniz is CEO of Northeast VisionLink, a company that specializes in the field of executive compensation and works with businesses to structure compensation plans. Northeast VisionLink also assists businesses in finding ways to grow beyond “organic” methods. Moniz is a national speaker on the topic of wealth management and executive compensation. He holds a master of science in financial ser vices (MSFS), and graduate certificates for specialized study in pensions and executive compensation, estate planning and financial asset management. Moniz is a Chartered Financial Consultant (ChFC) and Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU). As a national speaker, Moniz has addressed groups, includ ing Harvard Medical School and the Society of Human Resource Management. Throughout his more than 30 years in the financial services industry, Moniz has provided advice based on timely research and recent developments within the industry. Moniz is also President/CEO of Northeast Wealth Management, a company that focuses on the needs of high networth individuals and professionals and tailors financial programs to help clients determine and progress toward their objectives.